The CSIRO’s National AI Centre, in collaboration with Google Cloud and co-working space Stone & Chalk, has launched a new AI competition in the hope of supporting Australian entrepreneurship around AI. Competitions like this are sorely needed in Australia, as the country continues to struggle to build a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship around technology.

The competition will take place over three months, during which startups will be given tools, resources and support to develop a prototype. Those prototypes will then be judged, with the winning app being granted AUD $300,000 worth of research and development support.

With Australia struggling to support startups in AI through traditional venture capital and the country at risk of losing talent and ideas in AI overseas, this competition aims to help build a culture of excellence and innovation in AI locally.

The value of encouraging innovative thinking and then funding AI development via this competition becomes clear when you consider that, on just about every metric, Australia is at great risk of falling behind on AI:

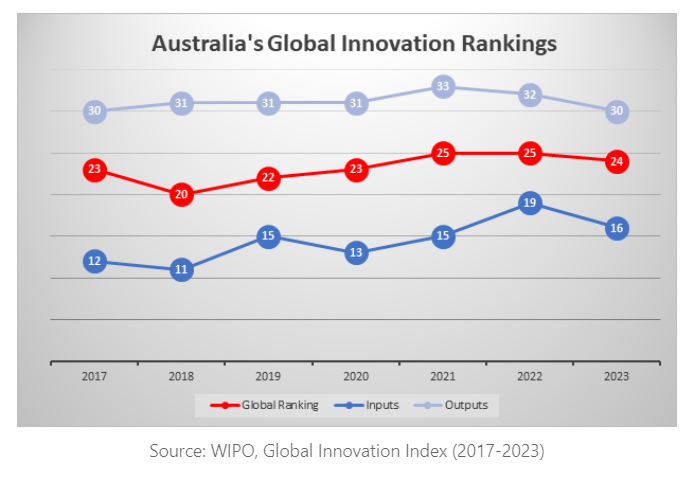

Most significantly, however, is that Australia continues to stagnate in the Global Innovation Index (Figure A). In 2023, Australia lifted one spot to 24. This places Australia at a lower innovation ranking than its global GDP ranking.

Nations such as the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Germany, China and Japan might be reasonably expected to rank higher. However, Australia is also rated lower than relatively small and modest economies such as Estonia, Iceland and Luxembourg.

Combined, the challenges mentioned above underscore that Australia is in a self-perpetuating cycle that undermines its ability to be innovative in emerging technology areas. Because opportunities for investment and innovation are relatively scarce, Australia has an ongoing “brain drain” of technical and entrepreneurial talent overseas. This was referenced as a priority by the new Australian Minister for Industry and Science Ed Husic in his first address in that portfolio, promising to make Australia a nation of “makers, not takers.”

SEE: Australia’s international standing in AI research is one indicator of strong local expertise and potential.

The traditional challenges Australia has had in retaining talent then mean there are fewer AI projects to support. Therefore, it becomes more difficult to secure funding, thus completing the cycle by then encouraging talent to again look overseas for opportunity.

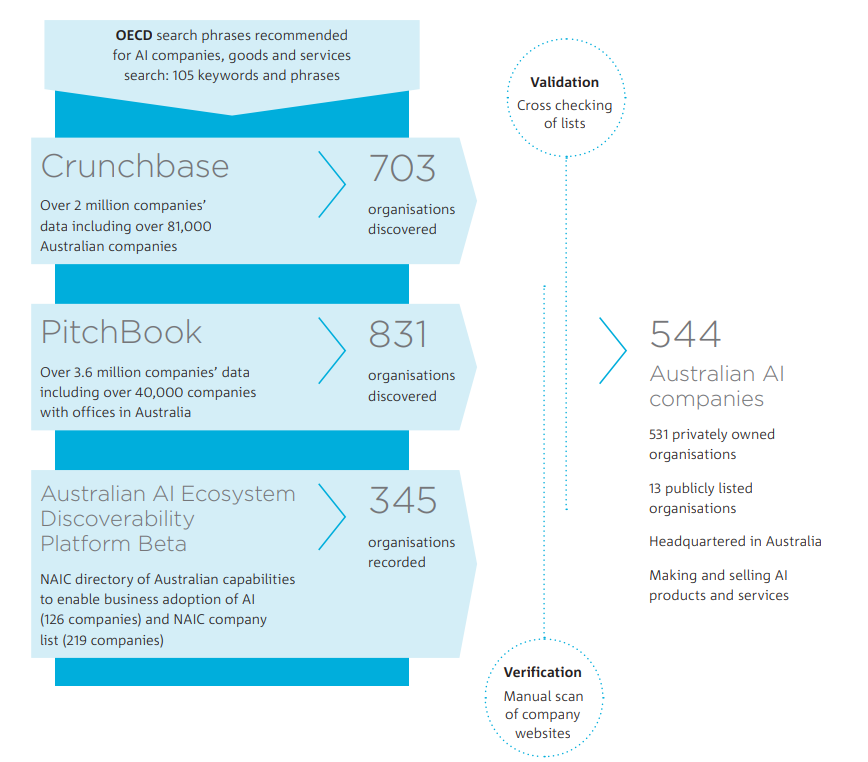

With startup funding crashing by two-thirds over the past year, it is becoming even more challenging to secure funding. This perhaps explains why, despite there being such runaway demand for AI globally, the number of Australian AI companies is currently a relatively modest 544 (Figure B).

However, the CSIRO-Google-Stone & Chalk competition, in offering AUD $300,000, is effectively providing the necessary money to an entrepreneur (most pre-seed funding rounds max out at $500,000). With the theme that the AI application must support the national interest, competitions like these have the potential to “fill in” for venture capital funding and ensure that Australia is generating innovation in the most critical areas.

While Australia is lagging in innovation globally and currently missing the boat on AI — one of the most critical fields of innovation of all — when it is able to build national infrastructure around a technology field, it can take a leadership position.

For example, Australia has invested heavily in developing its space program and, in 2021, generated AUD $4.5 billion across 600 companies. By 2030, that is expected to rise to $12 billion in economic activity.

Meanwhile, the Australian National Quantum Strategy, which focuses on the quantum computing opportunity, is expected to add AUD $6.1 billion to Australia’s GDP by 2045 and employ 8,700 by 2030.

Both space and quantum computing are deep tech fields that demonstrate Australia has the resources and skills to commercialise the most advanced technologies when the infrastructure and investment support the development of a local industry.

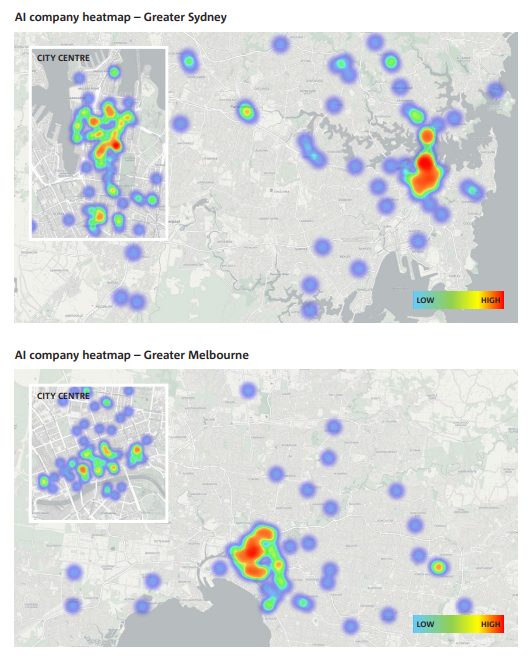

There are positive signs in the Australian market, too. One of the critical elements to building a healthy innovation-based sector is having a “cluster” of companies evolve. This is fundamentally what drove the growth of innovation centres such as Silicon Valley.

As CSIRO research shows, that clustering effect for AI-based companies is emerging in both the Sydney and Melbourne CBDs (Figure C).

The question is just whether Australia can develop the infrastructure to capitalise on the AI opportunity before other innovation centres around the world can establish an incumbency position in the field. There is an urgency to develop the local AI environment, and competitions such as the CSIRO-Google-Stone and Chalk are aiming to support that acceleration.