Another global chip shortage could be looming, with a new report predicting skyrocketing demand for AI-related products and services that suppliers may struggle to meet.

AI workloads could grow by between 25% and 35% annually up to 2027, according to consultancy Bain and Company. However, a demand increase of just 20% has a high likelihood of upsetting the equilibrium and plunging the world into another chip shortage.

“The AI explosion across the confluence of the large end markets could easily surpass that threshold, creating vulnerable chokepoints throughout the supply chain,” the authors of the Global Technology Report 2024 wrote.

Our hunger for AI will also necessitate the building of larger data centres with over a gigawatt of capacity. Existing data centres tend to be between 50 and 200 megawatts.

Combining the demand for AI infrastructure and AI-enabled products, the market for AI software and hardware is expected to grow between 40% and 55% annually over the next three years.

If large data centres currently cost between $1 billion and $4 billion, in five years they could reach between $10 billion and $25 billion, the report states. This results in a total AI market prediction of between $780 billion and $990 billion (£584 billion and £741 billion) for 2027.

SEE: Gartner Predicts Worldwide AI Chip Revenue Will Gain 33% in 2024

To sustain this rising demand, the supply chain for AI components must be able to scale up at the same pace. But, in reality, the chain is more like a complex spider’s web, with the chip raw materials at the centre.

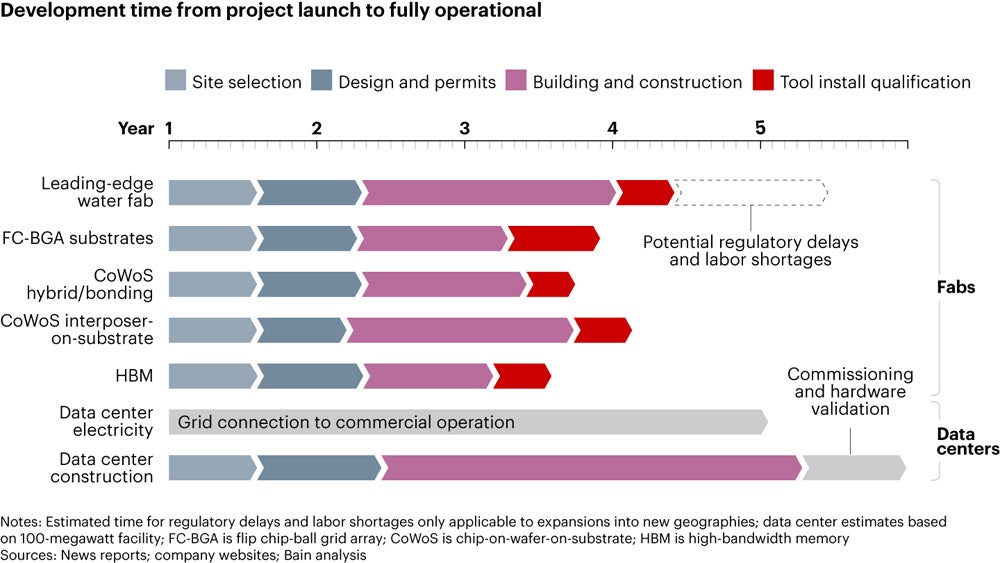

In one direction are the fabs and infrastructure required to scale up chip production, and another is the data centres needed for the AI products to function. Each has a lead time of between three-and-a-half years to over five years, according to Bain, posing a significant blocker for keeping up with demand.

Bleeding-edge fabs that manufacture the most advanced chips are the most vulnerable link, according to the report. They will need to raise their output by between 25% and 35% between 2023 and 2026 to keep up with the predicted 31% and 15% sales growth in PCs and smartphones respectively.

Up to five more bleeding-edge fabs would need to be constructed to keep up, costing an estimated $40 billion to $75 billion.

There is also the supply chain involved in turning chips into smartphones and PCs with on-device AI functionality, such as Apple Intelligence devices, which are growing in popularity as consumers have a greater desire for data security.

SEE: Gartner: AI-enabled PCs to Dominate Laptop Options for Businesses

Indeed, the silicon surface area in the average notebook core processing unit and smartphone processor have already increased by 5% and 16%, respectively, to accommodate for the on-device neural processing engines. Bain predicts these products could increase the demand for upstream components by 30% or more by 2026.

Packaging is another arm of the web, and if GPU demand doubles by 2026, suppliers would need to triple their production capacity. Plus, various power and cooling requirements link every part of the process to utility companies, which will also need to scale to demand.

Since the inception of the current generative AI boom, chipmakers have thrived. Leading graphics processing unit seller NVIDIA announced record revenues of $30 billion (£24.7 billion) in the second quarter of 2024, and has a stock market value of over $3 trillion (£2.2 trillion). Switch manufacturer Broadcom and memory chip maker SK Hynix have seen similar success.

SEE: Nearly 1 in 10 Businesses to Spend Over $25 Million on AI Initiatives in 2024, Searce Report Finds

These record profits have been realised by only a handful of core companies that control large portions of the supply chain. NVIDIA, an American company, designs the majority of GPUs that are used to train AI models. However, they are manufactured by Taiwan’s TSMC. TSMC and Samsung Electronics are also the only two companies that can make the most cutting-edge chips on a large scale.

But it has not always been plain sailing within the industry. A global chip shortage was sparked in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Supply issues amongst this relatively small number of companies continued for over three years, impacting industries such as consumer electronics and AI.

Even prior to the pandemic, the semiconductor supply chain was on shaky ground due to a series of events, including trade wars between the U.S. and China, and Japan and Korea, impacting commodity pricing and distribution. In addition, natural disasters, such as a drought in Taiwan and three plant fires in Japan between 2019 and 2021, contributed to raw material shortages.

“Extreme weather, natural disasters, geopolitical strife, a pandemic, and other major disruptions over the past decade have made abundantly clear how supply shocks can severely limit the industry’s ability to meet demand,” the Bain and Company report states.

It’s not just a lack of manufacturing capacity that could lead to a second global chip shortage.

“Geopolitical tensions, trade restrictions, and multinational tech companies’ decoupling of their supply chains from China continue to pose serious risks to semiconductor supply. Delays in factory construction, materials shortages, and other unpredictable factors could also create pinch points,” the report states.

The U.S., for example, has applied chip-related export controls on the sale of semiconductors to China, as well as the Netherlands and Japan. The U.K. also blocked the majority of license applications for companies seeking to export semiconductor technology to China in 2023.

China’s Ministry of Commerce also announced it would implement export controls on gallium and germanium-related items “to safeguard national security and interests.” These rare metals are essential in chip production, and China produces 98% and 54% of the world’s supply of gallium and of germanium respectively.

Governments worldwide are also spending billions of dollars to boost their own capacity for semiconductor production, with a primary reason being to reduce their reliance on other countries. However, data security also plays a part; by keeping the supply chain within their borders, authorities can better protect against espionage and cyber attacks.

In 2022, the U.S. passed the CHIPS Act, to provide needed semiconductor research investments and manufacturing incentives as well as reinforce America’s economy, national security, and supply chains. The White House has also launched a blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights to help regulate AI domestically and invested in the proof-of-concept for shared national AI research infrastructure.

Intel, TSMC, Texas Instruments, and Samsung — the world’s largest memory chipmaker — have all announced plans to build fabs in the U.S.

In August 2023, it was announced that the U.K. government will devote £100 million ($126 million) to fostering AI hardware development and shoring up possible computer chip shortages. Just this month, Amazon Web Services announced plans to invest £8 billion on data centres in the country over the next five years.

SEE: UK Government Announces £32m for AI Projects After Scrapping Funding for Supercomputers

The European Union offered €43 billion ($46 billion) in subsidies to boost its semiconductor sector with its European Chips Act, which was adopted in July 2023. The bloc also has the lofty goal of producing 20% of the world’s semiconductors by 2030,

But Anne Hoecker, head of Bain’s Global Technology practice, said that the quests for data sovereignty will be “time-consuming and incredibly expensive.”

She said in a press release: “While less complex in some ways than building semiconductor fabs, these projects require more than securing local subsidies. Hyperscalers and other big tech firms may continue to invest in localized AI operations that will ensure significant competitive advantages.”

The Bain report adds that small language models with algorithms that use RAG, or retrieval-augmented generation, and vector embeddings, could stand to benefit from data sovereignty, as they handle a lot of the computing, networking, and storage tasks close to where AI data is stored.

The Bain report outlines some recommendations for companies that utilise semiconductors on surviving another global chip shortage:

The report’s authors wrote: “Executives may still feel weary from the semiconductor supply disruptions spurred by the pandemic, but there’s no time to rest because the next big supply shock looms. This time, however, the signs are clear, and the industry has a chance to prepare.

“The path forward demands vigilance, strategic foresight, and swift action to reinforce supply chains. With proactive measures, business leaders can ensure their resilience and success in an increasingly AI-enabled world.”