A joint cybersecurity advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Department of Health and Human services and Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center was recently released to provide more information about the Black Basta ransomware.

Black Basta affiliates have targeted organizations in the U.S., Canada, Japan, U.K., Australia and New Zealand. As of May 2024, these affiliates have impacted more than 500 organizations globally and stolen data from at least 12 out of 16 critical infrastructure sectors, according to the joint advisory.

Recent security research indicates ransomware threats are still high, and more companies are paying the ransom demands to recover their data.

Black Basta is ransomware-as-a-service whose first variants were discovered in April 2022. According to cybersecurity company SentinelOne, Black Basta is highly likely tied to FIN7, a threat actor also known as “Carbanak,” active since 2012 and affiliated with several ransomware operations.

Rumors have also spread that Black Basta might have emerged from the older Conti ransomware structure, yet cybersecurity company Kaspersky analyzed both code and found no overlap. The rumors are mostly based on similarities in the modus operandi of Conti and Black Basta, yet without solid evidence.

Black Basta affiliates use common techniques to compromise their target’s network: phishing, exploitation of known vulnerabilities or the purchase of valid credentials from Initial Access Brokers. Black Basta was deployed on systems via the infamous QakBot.

Once inside the network, the affiliates use a variety of tools to move laterally through the targeted network to steal sensitive content and then deploy the ransomware (double-extortion model). Common administration or penetration testing tools — such as Cobalt Strike, Mimikatz, PsExec or SoftPerfect, to name a few — are used to achieve this task.

A variant of Black Basta also targets Linux-based VMware ESXi virtual machines. The variant encrypts all the files in the /vmfs/volumes folder that stores all the files for ESXi’s virtual machines, leaving a ransom note after the encryption.

Once the ransomware has been deployed, a ransom note is spread on the systems. The ransom note contains a unique identifier the organization needs to contact the cybercriminal via a Tor link.

A countdown starts on the Black Basta Tor site, exposing company names and information about the data Black Basta owns. Once the timer gets to zero, the stolen data is being shared.

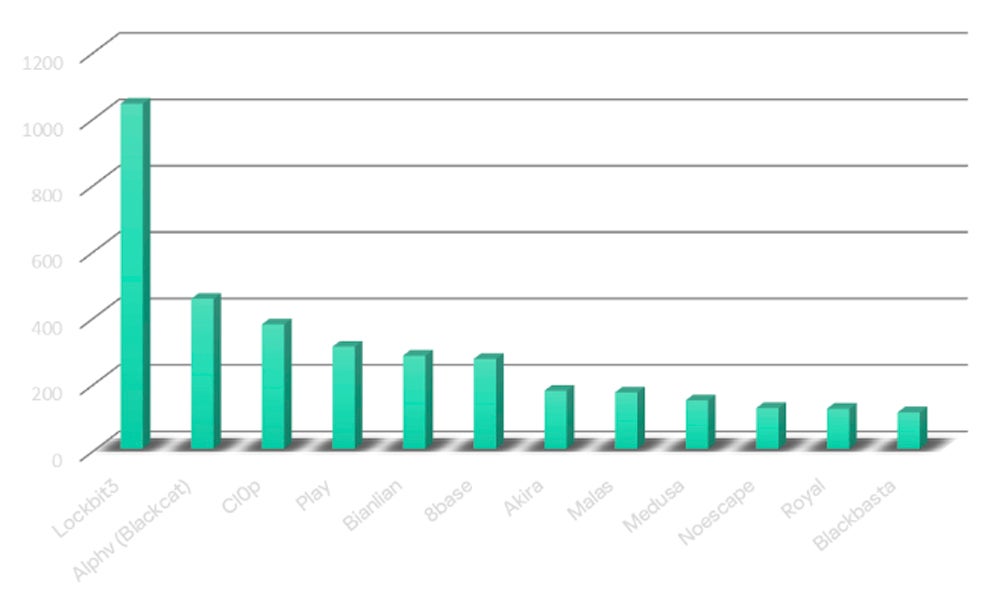

According to Kaspersky in its latest findings about the state of ransomware in 2024, Black Basta is ranked the 12th most active ransomware family in 2023, with a 71% rise in the number of victims in 2023 as compared to 2022.

Kaspersky’s incident response team reports that every third security incident in 2023 was related to ransomware.

SEE: In 2022, Black Basta was considered one of the most dangerous and destructive ransomware groups

In addition, the researchers noted another important trend observed in 2023: Attacks via contractors and service providers, including IT services, became one of the top three attack vectors for the first time. These kinds of attacks allow cybercriminals to spend less effort on the initial compromise and lateral movements and often stay undetected until encryption of the systems is done.

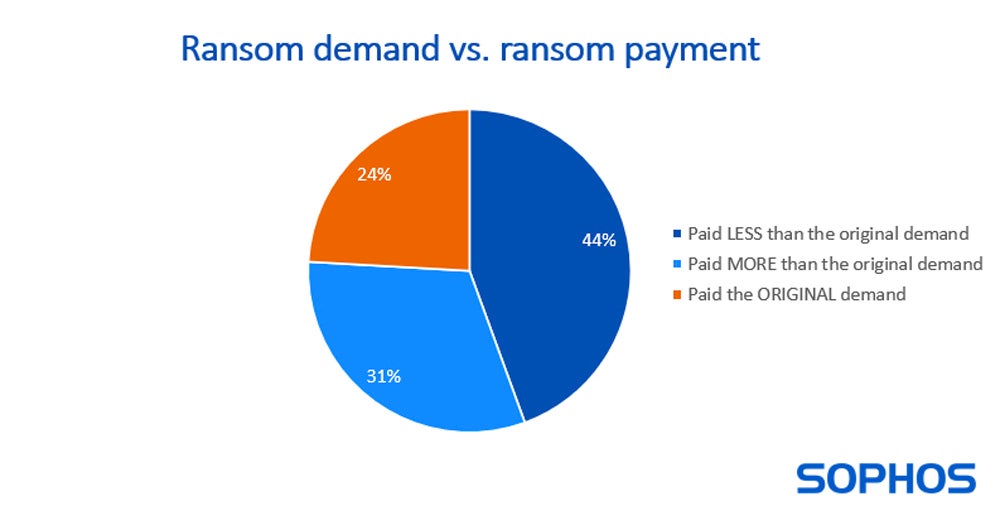

Cybersecurity company Sophos in its yearly state of ransomware survey noted that, for the first time, more than half (56%) of the organizations that had fallen to ransomware admitted they paid the ransom to recover their data in 2023.

For the organizations that decided to pay, 44% paid less than the original ransom amount, while 31% paid more.

Recommendations from CISA to all critical infrastructure organizations are the following:

More mitigation techniques are available in the #StopRansomware Guide from CISA.

Disclosure: I work for Trend Micro, but the views expressed in this article are mine.